Uncertainty Avoidance. What exactly is it?

With around 8 billion people in it, the world is a big place. It’s huge.

Ironically, the world feels smaller than ever before. Due totechnology, we are now able to communicate almost immediately with people from all around the world.

This has created new opportunities for collaboration. Whether it’s in the realms of business, music, art, or education, we can now work with people from across the world.

Nice.

Cultural differences (and similarities)

As access to the internet has become more common around the world, national cultures have started to become more and more alike. Essentially, so many of us consume media from the same sources, and we start to adapt things into our own culture.

However, every person on this planet still has their own culture. Whether it’s a national culture, organizational culture, or family culture, these cultures deeply affect our thoughts, decisions and actions.

At its core, culture is like a set of unwritten rules (or informal norms) that dictate how we should behave in order to fit in. A culture builds a common background which makes communication and interaction with each other easier.

As a result, understanding different cultures and cultural differences has become crucial for the success of day-to-day business practices.

Learning how to unlock these cultural differences and use them effectively can ensure success.

The key to all this may lie in a theoretical framework that is over 40 years old.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions

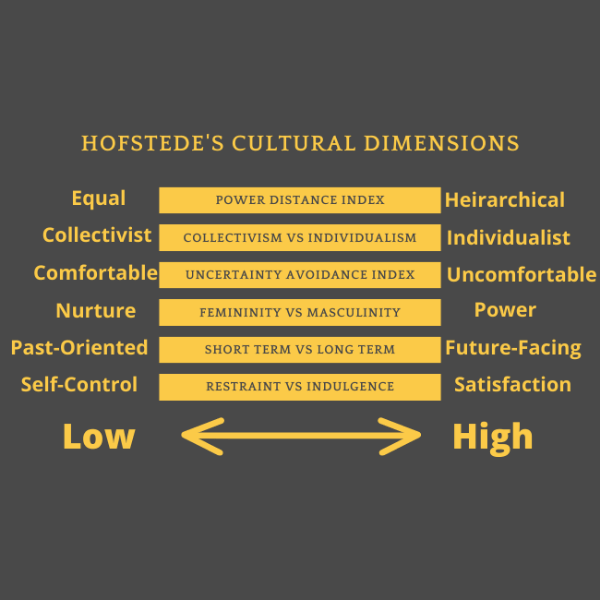

In 1980, Geert Hofstede came up with a way to look at how cultures differ. He worked out six major elements that contribute to how any given culture operates.

The combination of these six elements (or dimensions) paints a great picture of how a group of people think and act.

We’re going to hone in on the ‘Uncertainty avoidance’ dimension, but first, it’s a good idea to understand how it fits into the rest of Hofstede’s dimensions:

- Power distance index

- Collectivism vs. individualism

- Uncertainty avoidance index

- Femininity vs. masculinity

- Short-term vs. long-term orientation

- Restraint vs indulgence.

Power distance index

The power distance index indicates how much a culture accepts inequality and differences in power within organisations.

An organisation here refers to any group of people. This could refer to a family, a business, government, or local community.

Cultures scoring high in the power distance index are more accepting of inequality in power, authority, rank. To an extent, they expect inequality in these regards.

Countries with a low power distance index expect equality of power. These cultures are more likely to avoid hierarchy and unquestioning loyalty.

Collectivism vs. Individualism

Collectivism and individualism relate to how much the people in a culture feel like independent individuals. In more individualistic societies, people tend to make their own decisions.

This doesn’t mean that they think only of themselves, but rather that they don’t take society’s expectations as seriously.

In collectivist cultures, people are more geared towards ensuring that they contribute to the society and culture at large. In these cultures, people tend to ‘know their place’ and will work towards ‘the greater good.’

Uncertainty Avoidance Index

The uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) is the most important of these indicators. It has to do with any given society’s tolerance for the anxiety around uncertainty.

Sorry — what?

This basically means that you get two main cultural types. You get high uncertainty avoidance cultures. These people don’t like unpredictability.

You also get low uncertainty avoidance cultures. These people are quite happy to just “go with the flow.”

This is, obviously, an oversimplified explanation. The way that the uncertainty avoidance index plays out in the real world is manifold and complex.

But more on that later.

(In the meantime, here’s a great website that includes approximately one metric ton of articles relating to uncertainty avoidance.)

Femininity vs. Masculinity

This one is fairly self-explanatory.

Traditionally, women are perceived as soft, nurturing, and emotional. Men are perceived as tough, confrontational, and logical.

This dimension has to do with how a culture expects men and women to act emotionally.

In cultures scoring high on the masculinity side, competition between genders is expected. Bigger is better, and you should crush your enemies in the dirt if it’ll benefit you. You might call these cultures “patriarchal societies”.

If a culture tends to score high on the femininity side, the genders are more emotionally similar. Competition is not celebrated. Empathy and understanding are more highly valued

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Orientation

This dimension has to do with how a society deals with the passage of time.

Short-term oriented cultures base their outlook on the past. They view the world as being much the same as it was in the beginning. The history of their society becomes their moral compass, and they base their decisions on the monuments of the past.

Long-term oriented cultures view the world as ever-changing. This makes preparation for the future super important. Most of their decisions are forward-facing.

Restraint vs. Indulgence

The indulgence dimension is all about appetite and how easily one is satisfied.

In indulgent societies, people pursue the good life. It’s considered good to have as much as you want. Life is about friends, good times, and doing what you like to do.

In a restrained society, life is viewed as being difficult. Duty to your nation, job, culture, or family is more important over freedom and satisfying your own desires.

How do these work together?

Many of Hofstede’s cultural insights are often closely related.

For example, many short-term oriented countries usually score higher on the uncertainty avoidance index. This is because they like to keep things as they have been for many years. Tradition is good, and it provides direction for the future. This also minimises the anxiety around uncertainty.

Another example would be how collectivist cultures often score higher on the power-distance index.

The reason for this comes down to the fact that accepting authority is deemed by many to be in the best interest of the country. Going against authority and traditional authority structures can be seen as selfish, with motives that go against the collective good.

The same relationship may be true for restrained cultures and collectivism. Indulgence is seen as selfish and going against the collective good. Moderation is lauded because it leaves more for everyone else.

What is uncertainty avoidance?

One thing is certain: The future is uncertain.

We all wish we could see what the future holds, but unfortunately, scientists are yet to invent the future-vision-o-matic 3000.

Some people handle this better than others. While people in one culture might enjoy the idea of taking risks and leaping blindly into unknown situations, people in another culture feel threatened by uncertain or unknown situations.

Wikipedia has a great definition:

“In cross-cultural psychology, uncertainty avoidance is how cultures differ on the amount of tolerance they have of unpredictability.”

They go on to sum it up in Geert Hofstede’s own words:

“The fundamental issue here is how a society deals with the fact that the future can never be known: Should we try to control it or just let it happen?”

Beautiful. I always enjoy Geert Hofstede insights.

Why is the uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) important?

If you understand the uncertainty avoidance index and how to apply it, you can unlock a world of possibilities.

Because we rely so much on international trade, this comes with a large amount of communication between people from different cultures. So much so that most companies could really use an intercultural management division.

Because cultural identity and background play such important roles in how we think and act, offending someone culturally can mess up an entire relationship.

By understanding the uncertainty avoidance dimension of cultures, we can quickly get a snapshot of the cultural differences between us. By being aware of our cultural diversity before we even engage with new people, we can easily avoid major mistakes.

Indicators of uncertainty avoidance

The levels of uncertainty avoidance in a given country or culture usually match up with other characteristics of that culture.

This is the reason that uncertainty avoidance is the most important of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Because uncertainty avoidance is so pivotal to a society’s cultural dimension, it gives a brilliant starting point for cross-cultural understanding.

Rules and laws

One of the major indicators of a nation or culture’s UAI is their rules. These rules can be both explicit (like formal rules that have been written down in a country’s constitution, or even in a company’s code of conduct document) and implicit (like informal rules in a workplace, family, or social setting).

In high uncertainty avoidance cultures, there tend to be lots of rules. There are formal rules that attempt to micro-manage any and every possible situation (including etiquette), and informal rules which relate to most possible social situations.

These rules have been put in place as a means to attempt to reduce the uncertainty surrounding new and unstructured situations. High UAI cultures tend to be more orthodox, with strong religious and cultural traditions.

In low uncertainty avoidance cultures, there seem to be far fewer rules. This comes from the fact that in these cultures, there is less anxiety around uncertainty. The social norms in these cultures tend to make individuals more relaxed in unknown situations.

Risk management

High UAI countries want to avoid risk-taking. Calculated risks are deemed more acceptable, but they will only be undertaken after a lot of research and planning has happened.

Low UAI countries are less risk-averse. This means that they are generally more comfortable with risk-taking. They usually implement change quicker, and are generally more flexible, with more of an appetite for the unknown.

Tradition

Communities with a high uncertainty avoidance index tend to be more traditional. Tradition, culture, and religion are predictable, and they provide a set of rules which make handling unknown situations easier.

In a low uncertainty avoidance culture, there is less value placed in tradition. These cultures tend to be more informal and closed-off.

High uncertainty avoidance cultures

Prototypical high uncertainty avoidance cultures have a number of characteristics that set them apart from low uncertainty avoidance cultures. Their culture contains many of these characteristics.

As a result, it’s very important for us to be able to recognise these characteristics as part of their identity, particularly if we come from a culture on the opposite side of the UAI spectrum.

Some of the tell-tale signs of prototypical high uncertainty avoidance cultures include:

- Rules. Whether it’s in the dining room or the boardroom, people in these cultures love having rules and guidelines. These rules can be formalised or informal. This helps to make unknown situations easier because there is a fixed way of doing just about everything.

- Stress. Life is stressful — and passionate. It’s generally acceptable to lose your temper in order to blow off steam, and it wouldn’t be strange to see people arguing loudly in the street.

- Structure. Education, life, and business are all handled in very structured ways. Structures and strategies for risk management (both formal and informal) are always in place. Just in case.

- Ritual. Fundamental religious rituals are commonplace in these societies. Orthodox Christianity, Catholicism, Islam, and Judaism are usually associated with high uncertainty avoidance.

- Conservatism. Most people in these cultures are highly traditional and resistant to new ideas and change. This provides a type of security for them, but it makes racism (and all the other -isms) more widely acceptable.

High uncertainty avoidance countries

Some of the highest uncertainty avoidance countries are:

- Greece

- Japan

- France

- Mexico

- Israel

- Germany

These countries have extremely high ratings on the UAI scale, with Greece topping the list at 112.

Low uncertainty avoidance cultures

Low uncertainty avoidance societies are usually identified by their “no worries” attitude to life the universe and everything. Whatever happens, happens.

Prototypically, low uncertainty avoidance countries are made up of cultural factors that make them take life as it comes.

Because of this, it’s very easy for conflict to arise between people with low uncertainty avoidance and people from cultures with a high uncertainty avoidance index. This can be particularly damaging to private and business relationships.

In order to avoid this, understanding each other’s points of view can help to avoid breakdowns in cross-cultural communication.

Some of the tell-tale signs of a prototypical low UAI culture include:

- Ambiguity. You don’t mind ambiguity and you’re mostly easygoing. There are fewer formal governing entities, and not many laws dictating every aspect of life — and you are cool with that.

- Lack of stress. You think it’s important to keep your cool even if you’re wildly angry inside.

- Less structure. Education, life, and business are all handled more informally. Things happen when they happen, and if you show up to a business meeting in casual clothes, it’s not a train smash.

- Diversity. You appreciate ideas and are willing to accept new ideas from different people.

Low uncertainty avoidance countries

Some of the lowest uncertainty avoidance countries include:

- Singapore

- Denmark

- Great Britain

- USA

Compared to the high uncertainty avoidance of Greece, Singapore is on the opposite end of the spectrum at 8 points!

Practical examples of uncertainty avoidance

Let’s imagine a few scenarios.

Scenario 1: Uncertainty avoidance in daily life

A bumper-bashing happens in rush-hour traffic. Both cars are damaged but neither driver is badly injured.

Imagine this happening in one of the highest uncertainty avoidance countries (like Greece or somewhere in Latin America). One can easily picture how this could end in a shouting match, lots of angry gestures, and possibly even a punch-up.

Now imagine this happening in one of the lowest uncertainty avoidance countries (like Singapore or England). Perhaps there might be a mumbled, “Paiseh”, or an “I didn’t see you there, old chap.” It’s hard to imagine any emotions more intense than this in the exchange.

Scenario 2: Uncertainty avoidance in business

You have a product that is a bestseller in your country with high levels of customer loyalty. How hard could it be to replicate that in a foreign country?

Imagine launching your product in France, a country with high uncertainty avoidance. There is a similar local product already on the market.

Oops.

Customers are wary of new products. They are comfortable with what they know and are therefore more brand loyal. There is a very low uptake of your product, and you end up losing a boatload of money.

Had you launched the product in Denmark, a country with low uncertainty avoidance, customers would be less likely to be brand loyal. It would be possible to cut into the opponent’s market share and make a nice profit.

Scenario 3: Uncertainty avoidance in politics

The local population of your town is unhappy with the local municipal government. The service delivery is not up to standard, and there have been rumours of corrupt dealings.

If you live in a country with high uncertainty avoidance, chances are that not much will be done about it.

Because high uncertainty avoidance societies are often more accepting of the status quo and are hesitant to implement change, they are less likely to protest the actions of their local elected officials.

Having people removed from office could lead to any number of unpredictable outcomes, so for these individuals, it seems to be more trouble than worth protesting or initiating widespread civic action to have them removed. Better the devil you know.

If you live in a country with low uncertainty avoidance, people tend to be more politically involved and motivated. As a result, your local population would be more likely to engage in activities that could lead to new governance. And they’d be cool with that.

The real value of uncertainty avoidance

The scenarios discussed in the previous section are only three, very simplified ways in which knowledge of uncertainty avoidance and the uncertainty avoidance index could come in handy. The real value of understanding uncertainty avoidance will only be discovered in the real world.

This is because every person on this planet is an individual.

Sure, there are large groups of people who are bound together under the same cultural values, customs, and traditions. But even within a culture, there are small differences.

If you can learn to read and interpret a person’s individual UAI, you will set yourself up for tremendous interpersonal skills. These skills can help you get along better with people, land business deals, manage staff more effectively, and even get on with your partner.

By understanding a culture’s levels of uncertainty avoidance (including your own), you will have a baseline measurement of expectations. These will help you gauge what people expect of you as a member of a certain culture, and. it will help you know what to expect from them.

Of course, uncertainty avoidance is just one factor to consider when looking at someone’s culture, but it can easily be one of the most important. Uncertainty avoidance is one of the largest pieces of a person’s “cultural pie.”

By understanding someone’s tendency toward uncertainty avoidance, you can understand what drives them, how they view the world, and, ultimately, how to treat them.

That’s why uncertainty avoidance is the most important of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions.

Of course, when writing this for a report, try to avoid talking about superficial things and always check for relevancy. Our guide for PESTEL analysis (which is highly relevant for business reports) can fill you in here.

To sum it all up

A chap by the name of Geert Hofstede came up with some dimensions that we can use to quickly gain insight into people’s cultures.

There are six of them:

- Power distance index

- Collectivism vs. individualism

- Uncertainty avoidance index

- Femininity vs. masculinity

- Short-term vs. long-term orientation

- Restraint vs indulgence.

One of the most powerful of these is number 3, the uncertainty avoidance index (UAI).

Countries and cultures with a high UAI don’t do well with change. They like to avoid any anxiety that comes from things changing.

Countries and cultures with a low UAI don’t mind change as much. They like to go with the flow.

High UAI societies try to minimize the anxiety that arises from change by implementing a few measures:

- Rules

- Tradition

- Conservatism

- Avoiding change (obviously)

Low UAI societies don’t worry as much about change, so they tend to:

- Have fewer rules

- Enjoy exploring new ideas

- Be more liberal

- Embrace change

Because of the differences between these two schools of thought, it is easy for tension to arise in multi-cultural settings and interactions.

In order to decrease tension and thereby improve communication, it is a good idea to understand the uncertainty avoidance index of anyone you may interact with. Uncertainty avoidance plays such a big part in culture that it can easily determine the difference between success and failure in any given interaction.

Uncertain about society?

If you’re uncertain about how the people around you think, don’t avoid it. Share this article via your social media platforms, and see what your friends think!

0 Comments

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.